ABC News

ABC News(WASHINGTON) — Health officials in Washington state are grappling with a measles outbreak, calling for an “all hands on deck” approach to stop the spread of the preventable virus.

ABC News(WASHINGTON) — Health officials in Washington state are grappling with a measles outbreak, calling for an “all hands on deck” approach to stop the spread of the preventable virus.

The state’s governor, Jay Inslee, declared a state of emergency on Friday after officials confirmed there were 31 cases of measles.

“Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease that can be fatal in small children,” Inslee said.

By Friday, there were 30 confirmed cases and nine suspected cases of measles in Clark County in southeastern Washington. One case was reported in King County.

The outbreak in Clark County is an “extreme public health risk that may quickly spread to other counties,” Inslee said.

Dr. Alan Melnick, the public health director for Clark County, expects the numbers to rise.

A major contributing factor? The rate at which people in his county have chosen not to get vaccinated, he said.

“All this stuff that we’re going through and the cost, the suffering and potential complications that we’re going through here are completely preventable through an incredibly safe, incredible effective, incredibly cheap vaccine,” he told ABC News. “That’s what frustrates me and keeps me up at night.”

What’s going on in Washington is not unique. Dr. Stephen Morse, a professor in the epidemiology department at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, said public health measures have become “a victim of their own success.”

“When nothing happens we assume there’s no danger but the reality is there’s measles all over the world,” he said.

Morse knows the dangers on a personal level; he had measles when he was 6 years old in 1957.

“The year I had it, another 500,000 kids in America had it. There were a significant number of deaths [but] most of us survived,” Morse said. “It was so common that you took it for granted that you had these childhood diseases.”

The disease is so rare in the U.S. that for many young doctors today, “their first measles case is a surprise to them because they haven’t seen it before,” he said.

How the measles vaccine works

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization, on average one person with measles will infect 12 to 18 people in a susceptible population, which is a population without prior exposure to the measles virus either through vaccination or natural infection.

The disease is highly contagious; 90 percent of susceptible individuals exposed to the airborne droplets will become infected. The infectious droplets can remain in the air for two hours, meaning that one can become infected during that time period even without person-to-person contact.

While the effects of the disease are fairly mild in the majority of cases, there are rare cases where complications including seizures and paralysis occurs. When patients suffer neurologic complications, the mortality rate is 10 to 20 percent, according to a study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The vaccine is highly effective at preventing infection. Ninety-nine percent of people who received two doses of the vaccine, which is recommended by the CDC, will develop immunity to the virus.

The CDC recommends that children get two doses of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine (MMR). The first dose should occur when the child is between 12 and 15 months old and the second dose between 4 and 6 years old.

Since widespread administration of the measles vaccine, which became available in 1963 according to the CDC, the prevalence of measles has decreased by 99 percent in the United States. There can, however, be sporadic outbreaks in isolated populations with low vaccination rates.

“It only takes one person to get it and a few people around them to not be protected,” Morse said.

Those who cannot be vaccinated can still benefit from living in an immunized population through what’s called “herd immunity.”

Herd immunity refers to protection of an entire community when immunity rates are sufficiently high. When this occurs, the likelihood of someone with a disease encountering someone non-immune is negligible, preventing the disease from spreading through the population.

For measles, herd immunity is achieved when 92 to 95 percent of the population is immune. This protects people who cannot be vaccinated, such as newborn babies and people with severely compromised immune systems.

“They’re like a wall,” Morse said in describing those who are vaccinated, “and the people who are not immunized are holes in that wall.”

The history of vaccine hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy is not a new phenomenon though it continues to be an issue. The WHO listed it as one of the 10 threats to global health that it hopes to tackle in 2019. The philosophical challenge to vaccines has been around since the discovery of the smallpox vaccine in the 1850s, when some people have viewed compulsory vaccines as a violation of their personal liberties.

Vaccines became more widely accepted during the 1900s as immunizations against polio, measles, tetanus, pertussis and tuberculosis led to decreases in child mortality rates. The favorable perception of vaccines from 1950 to 1980 facilitated what many see as one of the greatest accomplishments of modern medicine: the eradication of smallpox in 1980.

In 1998, Andrew Wakefield, a former British physician who lost his medical license for professional misconduct, according to the British General Medical Council, published a fraudulent study of a small group of only 12 children suggesting a link between autism and the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine. This paper has since been retracted and discredited but not before setting off a crisis of vaccine mistrust.

Today, vaccine hesitant individuals represent a diverse group, according to researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Some lack sufficient knowledge about vaccines, some lack experiences with vaccine preventable diseases and others hold strong philosophical or religious beliefs about vaccines.

“There are a lot of good reasons why we shouldn’t take it for granted,” Morse said of vaccines.

Outbreaks in the U.S.

In 2018, there were 17 measles outbreaks with a total of 349 cases.

Three outbreaks in New York and New Jersey occurred within Orthodox Jewish communities where someone was infected during travel to Israel. Officials feel these outbreaks contributed to a higher than usual number of cases in 2018, according to the CDC.

In 2015, a large, multi-state outbreak was linked to an amusement park in California with 147 people infected. In 2014, an outbreak among unvaccinated Amish in Ohio resulted in 383 cases, per the CDC.

While the number of cases in Clark County have not reached triple digits yet, the outbreak there is not finished.

The ongoing threat in Clark County

On Thursday, there were 25 confirmed cases of measles and 12 suspected cases. By Friday the numbers jumped to 30 confirmed cases and nine suspected cases.

“Wiping down the classrooms every day won’t do the trick — you’d be having to wipe down the classrooms probably continuously,” Melnick said.

He said the only effective way to prevent the spread of measles is a long-term solution.

“I think the best thing we can do to prevent this is to have the vaccination rates higher,” Melnick said.

According to the latest Clark County data, 76.5 percent of the county’s 5,680 kindergarteners had complete immunizations in the 2017-2018 school year.

That marked a significant drop in recent years. The county’s kindergarteners had an immunization rate of 91.4 percent more than a decade ago.

Clark County is far from the worst in the state; it has the sixth lowest complete immunization rate. In San Juan County, only 47 percent of kindergarteners got their complete immunizations.

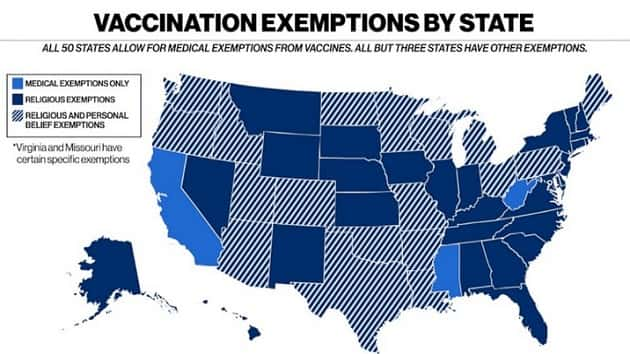

All states allow for medical exemptions to vaccines but there are 30 states that allow for religious exemptions and 18 others that allow personal belief exemptions.

Washington state is one of those 18 states. According to Clark County data, 7.9 percent of kindergarten students were exempted from immunization last year. The reason? Personal exemptions.

Melnick, like so many in medicine, touts the need for vaccines.

“It’s not just the CDC and the government — it’s basic science,” Melnick said. “For me it’s not controversial at all, but there’s broad scientific consensus that vaccines are essential.”

Erica Orsini, MD, is a resident physician in internal medicine and a member of the ABC News Medical Unit.

Copyright © 2019, ABC Radio. All rights reserved.