AlpamayoPhoto/iStock

AlpamayoPhoto/iStockBy IAN PANNELL and DAVID R MERRELL, ABC News

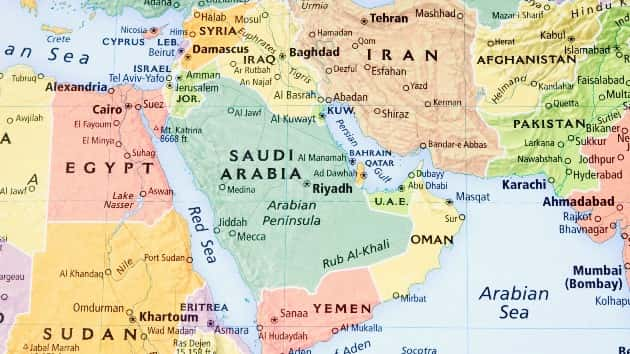

(NEW YORK) — Syria and Yemen face potential devastation if a large-scale outbreak of the novel coronavirus hits the war-torn regions, according to humanitarian aid organizations.

“The COVID-19 pandemic threatens to be a global socio-economic earthquake. It will be felt acutely in the region’s conflict zones, where millions are already coping with little or no health care, food, water and electricity, lost livelihoods, rising prices and destroyed infrastructure,” the International Committee of the Red Cross warned.

“The deliberate bombing of hospitals for nine years has devastated a health care system already ruined by the war,” Dr. Wasim Zakaria, one of the few doctors left in the rebel-held territory of Idlib, Syria, told ABC News. “Many physicians have lost their lives. That created a shortage in health care workers.”

Syria has only seen a few dozen confirmed cases of COVID-19, but Zakaria believes the real toll is much higher.

“I myself have seen 30 to 40 patients with symptoms of COVID-19 that sought treatment in multiple hospitals in areas of Idlib,” he said.

While all of those patients tested negative for the coronavirus, doctors have been unable to verify the results by retesting patients, due to the shortage of supplies.

“We haven’t seen the explosive outbreaks yet, but we can be very confident there are significantly more cases than we have been able to detect,” Dr. Rick Brennan, the World Health Organization’s regional emergency director for the Eastern Mediterranean, said in a video call with ABC News.

“One of the biggest problems with those tests is not the test itself, it’s how well the sample is taken,” Brennan said. “You need a nasal swab that goes to the back of the nose, or you can do that in the back of the throat. People gag a lot, and if the worker isn’t particularly well trained you can get a false negative test.”

Syria’s nine-year war between Bashar al-Assad’s government and rebel forces has come to a pause, the factions reaching a truce just before the pandemic was declared. Some refugees are taking the opportunity to make the difficult decision to return home, fleeing crowded camps where the risk of falling ill is high.

“It’s an incredibly challenging choice that families need to make,” said Brennan. “Do I stay in a place where I’m at a greater risk for catching COVID? Or do I move to a place where I’ve got more space and better water supply, but the security is much more questionable?”

The United Nations is calling for a global ceasefire “to prevent a major health crisis from further ravishing conflict zones.” There is evidence fighting has subsided in some areas, like Syria, but that’s not the case in Yemen, where a ceasefire between the U.S.-backed Saudi coalition and the Houthis, a rebel group backed by Iran, is barely standing.

“Airstrikes and fighting are increasing in Yemen amidst announced ceasefire, disrupting efforts to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in a country already facing severe hunger and the oncoming cholera season,” according to the International Rescue Committee.

More than half of Yemen’s health care facilities are closed or only partially functioning, according to a 2016 WHO study. Dr. Abdulsamad Abo-Taleb of Yemen’s Bani Houat Medical Center said things have gotten even worse.

“Yemen is under a heavy war from the coalition since five years, and most of the medical centers and the facilities of the health in Yemen were destroyed, some of them totally, especially in the northern part of Yemen and in the coastal region of Yemen,” Abo-Taleb said. “So, if coronavirus appeared in Yemen that would be, really, a disaster.”

He said the ceasefire is just propaganda on TV.

“On TV we are hearing this nice song of cease-fire, but at the same time, that night they announced the ceasefire in Yemen, they struck Sana’a with more than 50 air strikes,” he added.

Yemen has only reported six confirmed cases of COVID-19, but experts believe that number will rise.

“The first case had no known contact with any other case, so we can be confident there are other cases and ongoing transmission,” Brennan said. “We expect to see a lot more”

Violence and the coronavirus are far from the only things people living in Yemen have to worry about. Conflict and hunger are vicious bedfellows.

“Of the 135 million people who go to bed acutely hungry, the vast majority, 77 million of those, are in countries affected by conflict,” Arif Husain, chief economist for the World Food Program, told ABC News in a video call. “So unless we take care of conflict, we are not going to take care of hunger.”

Mohammed Al-kateeb Yahia, an aid worker with Building Foundation for Government in Yemen, gave ABC News cameras a tour of a medical facility where children were visibly malnourished. He said many more people who need help may have stayed away from the clinic out of fear of COVID-19.

“People are afraid from coronavirus and are not coming to this clinic,” he said. “This clinic is usually very, very crowded with 60 to 80 patients a day.”

Getting aid to these vulnerable populations can be especially difficult, due to the various factions in control of different areas.

“First and foremost, it is the war-affected places where supply chains don’t work,” Husain said. “You have about 30 million people who are stuck in these places and they’re not going to be able to get out of there. And we need to make sure that we continue to provide humanitarian assistance to them.”

Aid groups are working to get supplies to the people who need it, but Brennan said politics are driving much of the decision-making.

“One of the biggest challenges is the global market failures for the PPE, for ventilators, we need an equitable distribution of those supplies and equipment to the low- and middle-income countries,” Brennan said. “We need wealthy countries to support the vulnerable countries.”

Copyright © 2020, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.