ABC News

ABC News(NEW YORK) — Lee-Ellen Macon had beaten breast cancer once.

So when she went to the doctor this spring with what she thought was a slight thyroid issue, and instead received a stage IV cancer recurrence diagnosis, she was terrified.

“That’s the worst cancer you can have,” said Macon, 57. “Hardly anybody can recover from that.”

Almost as scary was Macon’s subsequent discovery: Her out-of-network deductible was $4,000.

That meant she had to pay at least that much out of pocket for care before her coverage kicked in. Many people don’t meet their deductibles every year.

“That’s a lot to have to pay, when you’re a teacher,” said Macon, who makes about $50,000 a year teaching eighth grade English and special education at a public school in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Combined with the more than $1,000 Macon already paid in premiums last year, she joined the ranks of Americans paying more than 10% of her income for health insurance.

According to a new report by The Commonwealth Fund, rising premium and deductibles contributions have outstripped wage growth over the past decade. More and more middle-class Americans are paying a greater percentage of earnings for health care.

The report analyzed survey data from 40,000 private-sector employers, as well as income data from the Census Bureau.

Median household income in the United States between 2008 and 2018 grew 1.9% per year on average, rising from $53,000 to $64,202.

But middle-class employees’ premium and deductible contributions rose much faster — nearly 6% per year over that same decade.

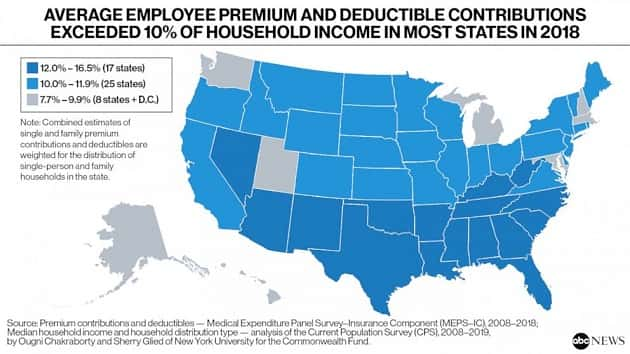

In 2008, middle-class workers spent about 7.8% of household income on premiums and deductibles. By 2018, that figure had climbed to 11.5%.

For workers in Mississippi and Louisiana, like Macon, those numbers look even worse.

In Louisiana, middle-class workers faced spending an average of 15.9% of their income on premiums and deductibles. In Mississippi, the most burdened state in the nation, middle-class workers faced the potential of spending 16.9%.

“The most cost-burdened families live in southern states,” said Sara Collins, lead author of the new report and vice president for health care coverage, access and tracking at The Commonwealth Fund.

In general, those states tend to have lower median incomes, so even if the sticker price for premiums and deductibles is lower than in higher-income regions, health insurance costs take up a greater share of Southerners’ income.

Hard trade-offs for middle-class Americans

For people without expendable income, contributing such a large proportion of wages to health insurance can force them to make hard trade-offs. Previous research by the Commonwealth Fund has found that when faced with high deductibles, some people skip or delay recommended medical tests or forego prescription medication.

“High deductibles can act as a financial barrier to care, discouraging people with modest incomes from getting services,” Collins said.

High premiums can be discouraging, too. At a certain level, lower-income individuals may decide to discontinue insurance altogether, especially now that the penalty for not having health insurance, once part of the Affordable Care Act, no longer exists.

“Many people in the mid-range of income distribution don’t have very much savings,” Collins added. “People may avoid care, but at some point it becomes inevitable.”

Unavoidable health expenditures drive others into debt.

For Macon, a mother of two adult children, bills piled up fast. Labs, PT scans, MRIs and oncologist visits quickly chewed through her meager savings.

The barrage of medical expenses meant Macon wasn’t able to get her car repaired and now has to rely on friends or charity organizations for rides to medical appointments. She’s worried about Christmas next month and whether she’ll be able to buy gifts for her family. Staying at home so much, she said, is isolating.

By June, she was out of money, and her sister started a GoFundMe campaign to help cover her medical expenses. Crowdfunding campaigns to cover health care expenses have increased in popularity as many have struggled with the rising costs. Like many others, Macon’s unfortunately has yet to reach its goal.

Then, in September, she took another financial hit: She had to go on short-term disability at just 60% of her former pay.

“It’s really wrecking my credit,” she said of her medical bills. “I’m behind on so many things. I can’t keep up with any payments that are being asked of me.”

In a few weeks, she’ll learn if the treatments she’s had are working. If they aren’t, she’ll have to go on palliative care, a frightening and expensive prospect.

“I do everything I can to try to stay calm,” she said. “But all the financial stress, on top of trying to heal, is ridiculous.”

Copyright © 2019, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.